THERE have been alarming trends around oral cancer in the UK in recent years. The number of cases has increased by almost a quarter, with the majority being oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). Over the next 20 years cases are expected to rise by a third, with predicted mortality rates of 38 per cent.

Historically, most people in the UK have developed OSCC as a result of smoking or alcohol. In the last 20 to 30 years there has been a steady increase in the numbers of individuals who have developed OSCC due to infection by oncogenic (cancer causing) types of human papillomavirus (HPV). The carcinoma due to HPV is most likely to be in the posterior tongue and/or upper pharynx. Patients with HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer do not have the traditional risk factors and tend to be male, aged under 50 and have a much better outcome than those who have similar cancer driven by tobacco and/or alcohol.

This article considers the key aspects of the initial recognition of possible OSCC and disease that may predispose to, or precede, such cancer.

Clinical features of likely oral cancer

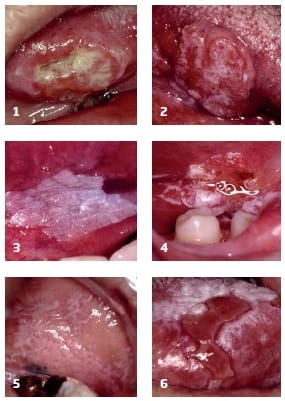

OSCC can give rise to a range of different features but perhaps the most typical is a solitary ulcer without an obvious local cause. Tumours tend to arise on the lateral border of the tongue or the floor of the mouth (Figures 1 and 2) but can be anywhere within the mouth. The ulceration is often deep, has a rolled margin and the surrounding mucosa may be white to red in colour. There can be necrosis of the tissues and the ulcer can be fixed to underlying structures. Oral cancer can give rise to swellings that are usually firm and the overlying mucosa can be abnormal – for example, speckled. Enlargement of lymph nodes in the neck is not always evident and the absence of this, despite the presence of a solitary ulcer/lump in the mouth, should not rule out a mouth cancer diagnosis.

Pain is the most likely symptom of oral cancer. Others include paraesthesia or anaesthesia of the lip or, less commonly, the tongue, loss of taste sensation, limited mobility of the tongue, or sudden onset of tooth mobility in one area of the mouth (e.g. if the tumour is on the gum.) Late features of cancer can include unexplained weight loss and anaemia.

The easiest aide memoire for diagnosis of all mouth cancers remains a solitary lesion that has no obvious local or likely infectious cause.

Clinical features of potentially malignant disease

Oral cancer is usually preceded by a variety of clinically apparent lesions which have cells displaying atypia, collectively termed oral epithelial dysplasia. As with oral cancer, most of these lesions are solitary. Such disease comprises the following:

Leukoplakia

These are solitary white patches that can arise on any surface of the mouth (but typically the buccal mucosa and floor of mouth) and are not likely to be caused by local trauma. Lesions can be sub-classified into homogeneous, when there is a uniform whiteness throughout the lesion (Fig. 3), and non-homogeneous, when there are elements of redness, background erythema (Fig. 4) and/or raised areas (verrucous leukoplakias). The majority of isolated white patches do not contain oral epithelial dysplasia but the more non-homogeneous the lesion the higher the risk of malignant transformation.

Erythroplakia

These isolated red patches of the oral mucosa or gingivae arise in the absence of a local cause (e.g. trauma or clinically evident candidal infection). Such lesions are rare but usually represent areas of severe oral epithelial dysplasia or carcinoma-in-situ. These can be an early manifestation of OSCC, so any patient with an isolated red patch that is not due to local trauma warrants immediate biopsy or referral to an appropriate centre.

Other potentially malignant disorders

Oral epithelial dysplasia and carcinoma-in-situ (when all layers of the epithelium have cellular atypia) can arise in a number of pre-existing oral disorders. The most common is oral lichen planus (OLP). This typically manifests as bilateral white patches affecting the buccal mucosae, gingivae and/or dorsum of tongue. The white patches (Fig. 5) are usually painless however, areas of erosion (erosive OLP) and ulceration (ulcerative OLP; Fig. 6) can give rise to painful symptoms. About one per cent or more of patients with OLP will develop clinically apparent oral epithelial dysplasia (i.e. leukoplakia or eythroplakia) and later OSCC, regardless of the type of OLP or how it has been managed.

Similarly, about four per cent of patients with oral submucous fibrosis

(OSMF; caused by exposure to a variety of agents, particularly arecoline

in areca nut) will develop OSCC, while around a quarter will have

leukoplakia. This disorder causes thinning, fibrosis and grey

pigmentation of the oral mucosa, particularly of the buccal mucosa

(left).

Similarly, about four per cent of patients with oral submucous fibrosis

(OSMF; caused by exposure to a variety of agents, particularly arecoline

in areca nut) will develop OSCC, while around a quarter will have

leukoplakia. This disorder causes thinning, fibrosis and grey

pigmentation of the oral mucosa, particularly of the buccal mucosa

(left).

Other potentially malignant disorders of the mouth include scleroderma, chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (and perhaps chronic hyperplastic candidiasis), rare instances of gross deficiency of iron, vitamin B12 and/or folic acid and some genetic disorders. Warts of the mouth are not caused by oncogenic types of HPV and thus are not considered potentially malignant.

The role of the GDP

A quick diagnosis is key and the box below provides some simple advice. If the clinical picture has significantly improved following removal of any likely local traumatic causes then generally this means the lesion was not cancer. However if there is no substantial improvement, or concerns remain, then specialist referral is warranted.

Assume all solitary persistent lesions without an obvious cause are suspicious

Patients should be informed of the possibility of a malignant lesion or disorder and the importance of attending the specialist appointment. It may also be appropriate to urge caution in googling symptoms as information found on the internet will often be inaccurate, alarming, biased and/or difficult to understand.

Contemporaneous notes should be recorded that provide an accurate indication of what the clinician observed, thought and actioned, as well as indicating that the patient was made aware of the possible diagnosis and was agreeable to the way forward. Simply writing “possible cancer, patient reassured” is inappropriate and opens the door to criticism.

Conclusion

Any solitary, odd and/or destructive lesion that has no obvious local cause and/or is present in a background of disease known to be potentially malignant should be considered as cancer until proven otherwise. Healthcare providers should inform patients of their thoughts, arrange timely and appropriate referral to a specialist, as well as maintain accurate and contemporaneous records.

Professor Stephen Porter is institute director and professor of oral medicine at UCL Eastman Dental Institute

Simple steps for diagnosis and management of oral cancer

- Assume all solitary persistent lesions without an obvious cause are suspicious.

- Remove all potential sources of local trauma and review (e.g. within two to three weeks). If the lesion has not reduced significantly within this time, regard it as suspicious and refer appropriately.

- Do not assume that a patient who does not smoke tobacco or drink alcohol cannot have oral cancer.

- Tell the patient of your clinical judgment and decision to seek specialist advice.

- Refer patients with lesions that are suspicious and have not responded to removal of likely local causes - but be sensible (multiple superficial ulcers are very unlikely to be cancer). Refer patients with non-healing extraction sockets.

- Ensure all relevant details are included in the referral and ensure it is marked urgent.

- When oral cancer is not in doubt, call the nearest appropriate specialist to gauge their thoughts and wishes.

- Referrals can be emailed provided principles of GDPR/Caldicott are followed.

- Keep accurate, contemporaneous and legible clinical notes (including a record of any correspondence with patients, relatives and specialists). If possible, keep clinical images of the lesions.

- Keep contact details of local specialists up-to-date.

- Know the wishes of local specialists regarding the early management of potential malignancy.

- Ensure staff are up-to-date with significant trends in the diagnosis of malignant/potentially malignant disease.

This page was correct at the time of publication. Any guidance is intended as general guidance for members only. If you are a member and need specific advice relating to your own circumstances, please contact one of our advisers.

Read more from this issue of Insight Primary

Save this article

Save this article to a list of favourite articles which members can access in their account.

Save to library