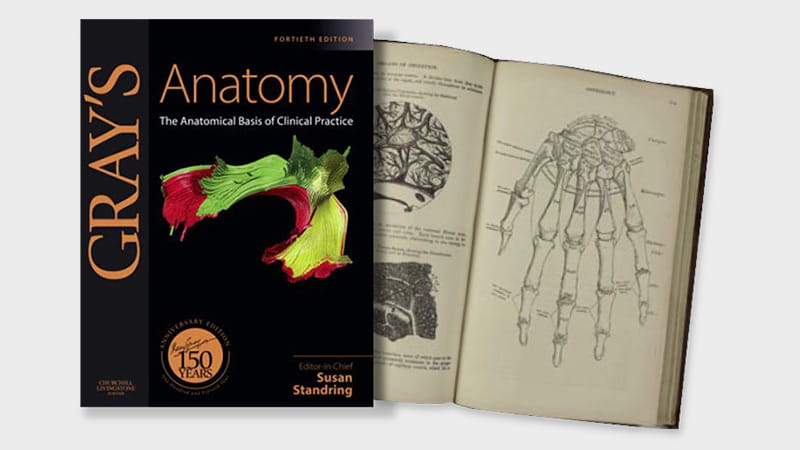

IT IS one of the most famous textbooks of all time. In 2005, a first edition sold for £4,920 at Christie’s in London. This autumn, as its publisher prepares to unveil a 40th edition, it will have been in continuous print for 150 years. This anatomical reference book is of such renown it has even lent its title to an award-winning American drama – in the television age, brand approval ratings don’t come any higher than that.

But do a little digging into the story of Gray’s Anatomy – first published as Anatomy, Descriptive and Surgical – and there soon emerges an interesting paradox. For while the eponymous Dr Henry Gray was certainly at the centre of the production of the book’s first edition, having written the words, at his side but unrewarded on its spine (and, from 1938, its modern title) was his colleague Dr Henry Vandyke Carter, who produced the illustrations that many suggest were the real root of the book’s runaway success.

“I believe anybody who says the words ‘Gray’s Anatomy’ should also know the name of Carter,” says medical historian Ruth Richardson, who has just completed a book on the subject, The Making of Mr Gray’s Anatomy. “It was the illustrations that sold the book.”

The book’s current editor-in-chief, Professor Susan Standring, agrees: “Why it’s not Gray’s and Carter’s I do not know. I think it’s dreadful that it’s not. Carter remains to be discovered. These days he would probably have been on the Today programme”.

Whereas many of the leading student anatomy texts at the time were pocket-sized manuals, measuring around 6” x 4”, with few illustrations occupying more than a third of the page, Gray’s broke the mould, coming in at 9.5” x 6” and containing much larger and clearer engravings. Carter also moved away from the trend for ‘proxy labelling’ – using tiny numbers or letters on the illustrations with a remote legend – and unified both name and structure on the drawings themselves.

The result was spectacular. “The new book sent the anatomy world reeling. Other textbooks went that way later, but it took them about 10 years to come back,” says Richardson. “Gray’s set a standard that was very hard to match, even for itself.”

An obscure genesis

No one is suggesting that Carter is turning in his grave at having missed out on primetime recognition in 21stcentury America, nor indeed that Gray deliberately diddled him out of his just rewards. The truth is that very little is known about the genesis of Gray’s – we don’t even know whose idea the book was. The publisher, J W Parker, owned the copyright and may well have commissioned the book himself.

What is known is that in 1855, Gray, who was on the teaching staff at St George’s Hospital Medical School in London, enlisted the help of Carter, whom he knew to be a gifted artist, to produce an accurate, affordable teaching aid. There followed 18 months of hard labour as the pair carried out the dissections that would form the basis of their opus and then produced its ground-breaking content. By the time of its publication in 1858, with a print run of 2,000 copies, Carter had pocketed his fee (a one-off payment) and set sail for India, for a new life in the medical service there.

Meanwhile Gray, who received a royalty of £150 per 1,000 copies, shepherded in a second, enlarged edition, before tragically succumbing to smallpox a year later, in 1861, at the tender age of 34. Carter was to live another 36 years, eventually dying in Scarborough, but he would play no more part in the book’s history.

‘The new book sent the anatomy world reeling. Other textbooks eventually caught up, but it took them about 10 years’

A century and a half and 39 editions from the first, the book’s worldwide standing is as strong as ever. Over the period Gray’s Anatomy has sold more than a million copies, and the 40th edition, weighing in at not much under a stone, has a whopping 1,700 pages, featuring 1,200 illustrations, and was put together by 10 section editors, 71 contributors and 62 reviewers from all the corners of the world. The book’s publisher, Elsevier, considers Gray’s, alongside The Lancet, as one of their most important brands. One of the main factors in its ongoing success over the years has been the commitment of its various editors to move with the times and to regularly update and amend the content.

The job of overseeing the most recent update has fallen to Susan Standring, Professor of Experimental Neurobiology at King’s College London, who is editor-in-chief for the second time. “It’s been fantastic,” she says. “I have a team of incredibly committed section editors, and we’ve amassed a fantastic team of contributors.” At the same time, she confesses: “It’s been as tough this time as it was for the 39th edition. It’s an enormous amount of work. It’s not my day job but it’s every night and every weekend.”

Standring has, in fact, been associated with the title for over 40 years, having won it as her sixthform prize in 1964 before going to medical school. She later did her PhD with Professor Peter Williams, who was an editor of Gray’s from 1973 to 1995. “I suggested to Peter while I was a post-doc that it might be good if the book had a bibliography and so I started by creating that,” she says. “I’ve been involved in every edition since then.”

Root-and-branch overhauls

Her long period of association has meant Standring has been involved in two of the pivotal editions, involving the kind of periodic root-and-branch overhauls that have helped to keep the book at the top of its genre. Peter Williams and Roger Warwick’s 1973 edition, the 35th, for which Standring created the title’s first bibliography, saw more than half the text newly written, with new commissions for nearly a third of the illustrations. There were also plenty of other innovations, in both content and style, in what some have called the ‘Pop Art edition’, that set the pattern for the next 25 years.

The next key overhaul coincided with Standring’s first stint as editor. As she explains: “The 38th edition had been out for quite some time when the book’s commissioning editor came to see me and asked me what I thought of it. I’m afraid I was extremely honest. I said I thought it had lost its way – it hadn’t really been revised and nobody really used it.”

She also said that if it was up to her, the book would be arranged in regions rather than by system, as clinicians, particularly surgeons and radiologists, don’t deal in systems. She continues: “He went off and consulted all around the world and came back and said, ‘Everyone agrees with you – will you do it?’ So I said yes, not realising quite what I was taking on”.

Today, she says she would love to have both systematic and regional approaches, as there’s a place for both of them, but “we just don’t have enough space”. Indeed, she admits, with the amount of information growing all the time – with more surgical detail than ever before – there has even been talk of having two volumes for the next edition.

As the story of this publishing phenomenon continues, one can’t help wonder what Gray and Carter would have made of it all. Despite the early successes, it is almost impossible to believe that either of them could have had any inkling of what they had started.

None of Gray’s text survives in the latest edition, nor any of Carter’s illustrations. But with the latest edition making ever more imaginative use of up-to-the-minute imaging methods and the boldest of full-colour illustrations, the example set by that first edition in terms of its visual authority is surely part of the continuing success story.

And while Carter’s contribution to the phenomenon has been somewhat overlooked, this July will see him finally begin to receive some official recognition, when a plaque is erected at his final residence in Scarborough. Ruth Richardson, for one, is delighted. “He hasn’t got a plaque in London, but Gray has,” she says. “Carter’s never had the credit he deserves, but he’s going to start having it now.”

- Gray’s Anatomy (Elsevier) will be published in September; Ruth Richardson’s The Making of Mr Gray’s Anatomy (Oxford University Press) will be published in October.

Adam Campbell is a freelance writer and regular contributor to Summons.

This page was correct at the time of publication. Any guidance is intended as general guidance for members only. If you are a member and need specific advice relating to your own circumstances, please contact one of our advisers.

Read more from this issue of Insight

Save this article

Save this article to a list of favourite articles which members can access in their account.

Save to library