BACKGROUND: Mr K is 51 years old and works in finance. He presents to his GP with an abdominal bulge in the left groin, with pain, especially on bending or lifting. He is diagnosed with an inguinal hernia and referred to a surgical unit.

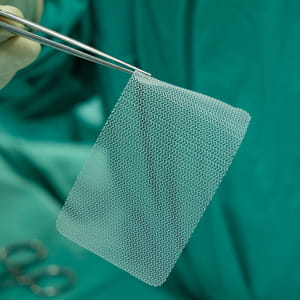

Mr K is put on a waiting list and 12 weeks later is admitted to hospital and undergoes a laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair, using surgical mesh. The patient is discharged after two days, with advice on pain relief.

Less than a month later he attends his GP complaining of persistent pain and some swelling in the left groin. Mr K is referred back to the surgical unit. An MRI reveals no problem related to the mesh and no recurrence of the hernia. The surgeon advises Mr K that there could be some fatty infiltration of the inguinal canal (cord lipoma) and this may be causing discomfort but she would be reluctant to embark on further surgery. She refers the case to a senior colleague.

A consultant surgeon reviews the MRI and in discussion with the patient advises open groin surgery and removal of the cord lipoma. Mr K agrees but requests a private referral to avoid having to wait. The consultant contacts a colleague – Mr J – who agrees to undertake the procedure. Mr J’s secretary contacts Mr K offering an appointment to discuss the treatment but the patient (wanting no further delay) opts for a quick admission.

Mr K is admitted for surgery and signs a consent form. Mr J undertakes open groin surgery and excises a small but elongated cord lipoma. The patient is discharged the next day but on follow up reports that the pain is no better and has in fact grown worse. Subsequent treatment including steroid injections and neurectomy are ineffective in relieving the pain. Mr K finds sitting for any long period uncomfortable and his mobility is reduced. He is later referred to a pain clinic.

Six months later a letter is sent by solicitors acting on behalf of Mr K claiming clinical negligence in the treatment provided by Mr J. It alleges that the patient was not informed that he would be undergoing open surgery, nor was there any discussion of the risks/benefits of the procedure. Mr K claims that had he been fully informed he would not have undergone the operation.

ANALYSIS/OUTCOME: MDDUS acting on behalf of Mr J reviews the case and commissions an expert report from a consultant surgeon.

In his response to the claim, Mr J states that in the letter from the referring NHS surgeon it was clear that the proposed treatment had been discussed and agreed with the patient prior to his requesting private care in order to avoid a prolonged wait. Mr J had offered to see Mr K in clinic in order to further discuss the operation but the patient opted for direct admission to the surgical unit.

Mr J states that his usual practice on the day of surgery is to have a quick word with the patient to ensure understanding of the procedure and to offer an opportunity for any last questions. The records show that a surgical consent form was signed but the operative method is not detailed nor is there any record of benefits and risks discussed.

The surgical expert opines that the decision to undertake open exploration and removal of the cord lipoma was appropriate. He notes that a consent form for the named procedure was signed but there was an assumption that Mr K was aware he was undergoing an open procedure and fully understood the risks/benefits. The expert states that in his view this constitutes a failure of informed consent and a breach of duty of care by Mr J.

In regard to causation (the consequences of the breach), the expert acknowledges that it would be up to a court to decide what Mr K might have done had he been fully informed about the open procedure and the risk of further pain and/or complications. Had he chosen more conservative treatment Mr K would still have endured persistent chronic pain.

MDDUS decides in agreement with the member to settle the case for a modest sum.

KEY POINTS

- Ensure the patient understands clearly what treatment is being proposed – this is the essence of shared decision-making.

- GMC guidance makes clear that the doctor providing treatment is responsible for discussing consent with the patient.

- Record what was discussed with the patient in regard to consent.

- Do not assume informed consent has already been secured – always confirm.

This page was correct at the time of publication. Any guidance is intended as general guidance for members only. If you are a member and need specific advice relating to your own circumstances, please contact one of our advisers.

Save this article

Save this article to a list of favourite articles which members can access in their account.

Save to library