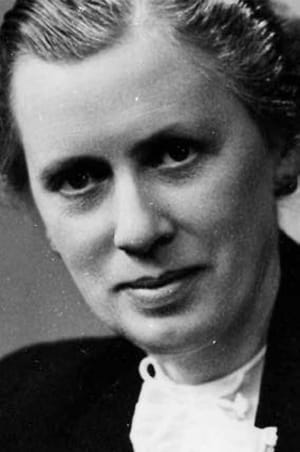

DUNDEE prides itself as a city of discovery and in recent years has worked hard to honour those of its citizens who have contributed to that name. Today in Slessor Gardens, behind the imposing Caird Hall, you will find a walkway paved with bronze plaques. Amongst these is one to Margaret Fairlie. As well as a short biography, the plaque depicts less obvious clues about her life and career – a frame of sea holly and wheat, a glimpse of the Eiffel Tower and a stylised atomic structure of radium.

Margaret Fairlie was born in Angus and grew up on a farm near Arbroath –hence the plants framing her plaque. She studied medicine at the University of St Andrews and University College, Dundee, graduating during the First World War. After holding various clinical posts in Dundee, Perth and Edinburgh, she worked at St Mary’s Hospital in Manchester, where she received much of her specialist training.

She returned to Dundee in 1919, where she would spend most of her remaining career. There, she ran a consultant practice for gynaecology, and the following year started teaching at the Dundee Medical School. In the mid-1920s, she joined the staff of Dundee Royal Infirmary and in 1936 was promoted to Head of Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Her appointment, however, was not met with universal approval, and one male colleague was disgruntled that the post had been awarded to a woman.

Although a gifted and diligent teacher, she also pursued an active clinical career. In addition to her core work at the infirmary in Dundee, Fairlie was visiting gynaecologist to all the hospitals in Angus and in the north of Fife. Like all in her specialty, she dealt with patients across a wide age spectrum and enjoyed all aspects of it. As an obstetrician, she helped set up Dundee’s first antenatal clinic.

One matron asked her: “Do you think if all the babies you delivered were laid top to tail they would reach from Dundee to Perth [some 22 miles]?”

“Yes – and heading for Scone [another 2.5 miles]!” was Fairlie’s quick reply.

As for her interest in the novel treatment of gynaecological malignancy, this was sparked by a visit in 1926 to the Marie Curie Foundation in Paris where she learned about the clinical applications of radium — hence the Eiffel Tower and atomic structures on her bronze plaque in Dundee. On her return, she pioneered its use in Scotland and conducted careful long-term follow up of her patients.

Thirty years later she would remark: “One aspect of my work which has given me especial satisfaction and delight has been my continuity with the patients who attend the radium follow-up clinic... some of whom have been coming for twenty years... The atmosphere at this clinic is one of trust, gratitude and mutual affection."

Her students, colleagues and patients found much to praise, but perhaps Fairlie's main claim to fame was to become Scotland’s first female professor. This, however, was not straightforward. In 1936 her appointment as head of department should have almost automatically made her eligible for the chair in obstetrics and gynaecology. However, it took the University authorities four years to come to terms with appointing a woman. Perhaps she was a victim of the political difficulties ongoing between Dundee and St Andrews Universities at the time, but it is also thought that the then Principal of St Andrews was particularly averse to the idea of a woman professor.

She was finally appointed to her chair in 1940, with the strong backing of the Directors of Dundee Royal Infirmary. At the time of her retirement in 1956, she remained the only female Scottish university professor. It would be another two years before the University of Edinburgh would appoint its first woman to a chair and a further 22 years before Glasgow would follow suit.

In her retirement Margaret was a keen gardener and an enthusiastic traveller. It was while in Florence in the summer of 1963 that she took ill for the last time. She returned home and was admitted to her former hospital where she died soon after. Today there is that bronze plaque on Dundee’s Discovery Walk, which includes words from one of her patients: “ ‘She gave me the will to live.’ Surely no higher tribute could be paid to a practitioner of medicine.”

Allan Gaw is a writer and educator in Scotland

Sources

- Baxter K. University of Dundee Archives.

- Richardson S. Glasgow Herald, 20 April 1956.

- Obituary. Glasgow Herald, 13 July 1963.

This page was correct at the time of publication. Any guidance is intended as general guidance for members only. If you are a member and need specific advice relating to your own circumstances, please contact one of our advisers.

Read more from this issue of Insight Primary

Save this article

Save this article to a list of favourite articles which members can access in their account.

Save to library